Probably, no block of marble had a more tortuous journey from quarry to piazza than Baccio Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus. A sculpture with 2 stories to tell – one is a Herculean myth. The other is its entanglement within the momentous upheavals in Florence’s transformation from a republican to a monarchical state.

Featured photo: The sculptures David by Michelangelo and Hercules and Cacus by Bandinelli guarding the portal of Palazzo Vecchio. Piazza della Signoria – Florence, Italy.

Table of Contents

A Sculpture Caught in the Throes of History

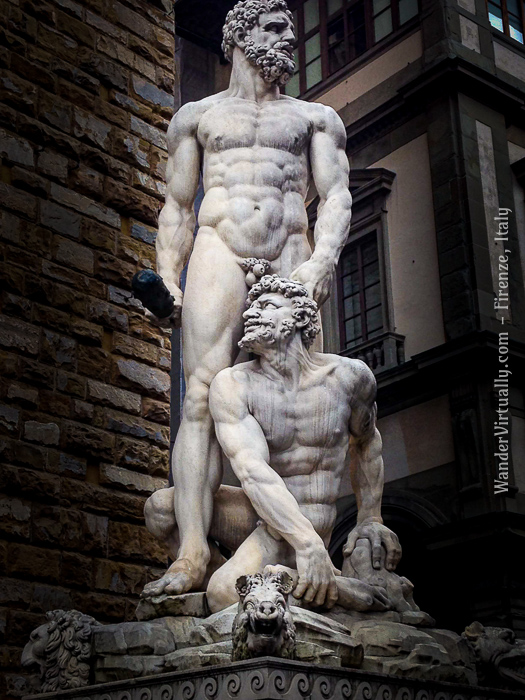

Baccio Bandinelli’s 10-foot colossus Hercules and Cacus comes to us with much political drama and artistic intrigue from 16th century Florence. The sculpture was conceived in 1507, started in 1525, and finally completed in 1534. It is located at the Piazza della Signoria of Florence, opposite Michelangelo’s David.

A Celebration of the Florentine Republic

The Florentine republicans were in high spirits at the start of the 16th century.

In 1494, they had just expelled the art-loving but tyrannical Medici for the second time. After 60 years of behind the scenes rule and manipulation, the Medici had become unpopular. The more democratically-inclined Florentines drove them out of Florence.

(Visit this page for an introduction to the Medici, or see Related Posts below).

In 1498, they finally rid themselves of the art-averse extremist Dominican friar, Savonarola. Florence had fallen under the sway of the puritanical priest, who had no love for the Medici nor the city’s frivolous art. But such puritanical repression was impossible to bear. The citizens hung and burnt Savonarola at the piazza.

And in 1504, they had just installed and celebrated Michelangelo’s colossal marble sculpture David – a work of art that they considered a symbol of Florence’s freedom.

Another Colossal Sculpture, Please

Things were looking good for the republic. A few years later, the republican leaders felt the need to have another sculpture opposite that of David standing guard at the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria (present-day Palazzo Vecchio). See Reference (13-i).

In 1507, they commissioned Michelangelo again for another colossal sculpture that would represent Florence overcoming tyranny (likely, both Medici and Savonarola flavors of tyranny). They ordered the Carrara marble to be quarried for the project.

However, Pope Julius II kept Michelangelo busy working on various Vatican projects in Rome. He was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling from 1508-1512.

So, Michelangelo was unable to put the chisel to the marble. And the block of marble was forgotten and sat in Carrara for the next 15 years.

The Return of the Medici

After 18 years in exile, the Medici triumphed over the Florentine republicans and regained control of Florence once again in 1512 with the help of papal and Spanish forces.

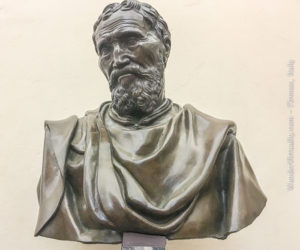

Years later, someone remembered the Carrara marble. To Michelangelo’s disappointment, Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici (who became Pope Clement VII) ordered Baccio Bandinelli to take over it in 1523. He wanted Bandinelli to produce a sculpture that symbolized the Medici vanquishing its enemies.

Meanwhile, Pope Clement VII told Michelangelo to focus on his architectural projects – the Medici mausoleum and library.

The Block of Marble Finally Gets a Life

Bandinelli immediately began to work on a Hercules conquering Cacus theme for the sculpture. But he had to abandon it halfway through when – for the third time – the Florentines expelled the Medicis from Florence in 1527. See Reference (12-i).

The rebellious republican Florentines again gave the half-worked marble to Michelangelo.

But before he could rework the marble, the Medici returned to Florence once again in 1530. This time, they were back for good: the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had installed them as the city’s hereditary monarchs.

Bandinelli got his hands on the marble once again and finally completed the 10-foot sculpture of Hercules and Cacus in 1534.

But Not Before It Attempted to Commit Suicide

According to the art historian Giorgio Vasari, when the block of marble was being transported from the quarry at Carrara to Bandinelli’s Florence studio in 1525, it fell into the Arno River.

It was so heavy that it lodged deep into the river sand and could not be moved. After much civil engineering effort – including diverting the course of the river – the workers finally extracted the block of marble from its muddy burial.

Once this incident became known, Bandinelli – who, apparently, was not very well-liked – became the butt of jokes. The story went around that when it realized it would be carved by Bandinelli instead of Michelangelo’s hands, the block of marble threw itself into the river out of despair.

Hercules and Cacus, Unveiled

Bandinelli unveiled his sculpture in front of the Palazzo della Signoria in 1534. According to Vasari, there was for 2 days, a multitude in the piazza who went to see the colossal work.

It had many detractors – mainly, republicans who lost out to the Medici, and Michelangelo’s friends who thought the commission was stolen from him.

However, the Medici seemed to have been very satisfied with Bandinelli’s work, and the message it was meant to convey. In addition to his monetary compensation, they awarded him with an estate to attach to his residence.

The Story of Hercules & Cacus: A Roman Tale

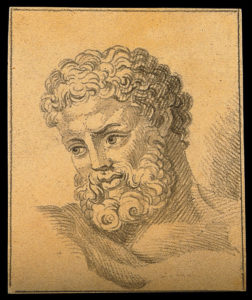

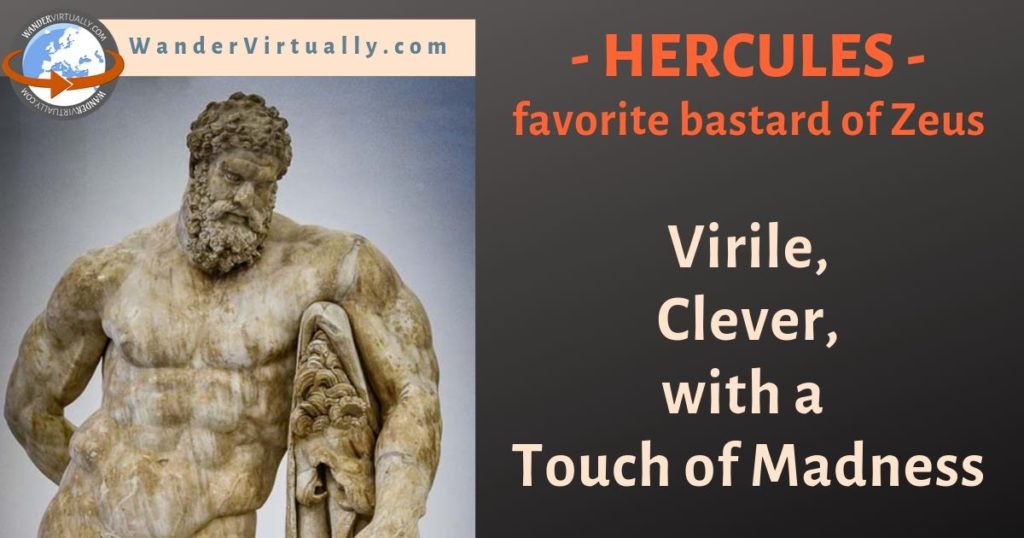

Hercules was a popular hero and demigod whose physical prowess and wit helped him overcome numerous monsters and bad actors. Many ancient and Renaissance-era leaders extolled his qualities and used him as their model of manhood and leadership.

While Hercules was Greek and his adventures were a Greek epic story set in the Bronze Age, ancient Roman writers decided to give him a Roman detour via one of his 12 Labors. They inserted into the 10th labor, the story about the hero’s encounter with Cacus in the land of the future Roman Empire.

(Visit this page for the story of Hercules and his 12 Labors, or see Related Posts below).

According to scholars, it is this “local” story of Hercules destroying Cacus, that appealed to the Medici. Through the sculpture, the Medici wanted to demonstrate their power over their enemies.

The Cattle of Geryon

For his 10th labor, King Eurystheus commanded Hercules to steal the prized cattle of the monster Geryon. This task involved traveling from his homeland in Greece, across the Mediterranean and all the way to Cadiz in Spain where Geryon and his herd of cattle lived.

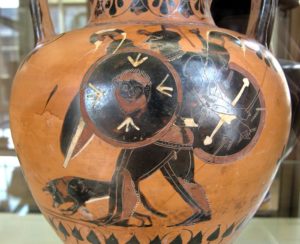

Geryon was a monstrous man who had one body with 3 heads, 3 pairs of arms, and 3 pairs of legs. Hercules overpowered him – as well as his minion which included the fierce 2-headed dog Orthus.

He then herded the cattle all the way to Italy on the way back to Greece.

In Italy, he sought the hospitality of Evander, the leader of a tribe of Greek transplants who had settled on the Palatine Hill long before the Trojan War.

After feasting with Evander, Hercules rested for the night.

Cacus Steals from Hercules

Now, there was a fire-belching monster that lived in a cave and plagued the Palatine lands of Evander. Virgil described the monster Cacus in his epic Aeneid:

“There th’ half-human shape of Cacus

made its hideous den,

concealed from sunlight and the day.

The ground was wet at all times with fresh gore;

the portal grim was hung about with heads

of slaughtered men, bloody and pale—

a fearsome sight to see.

Vulcan begat this monster,

which spewed forth dark-fuming flames

from his infernal throat,

and vast his stature seemed.”

– Virgil, Aeneid

While everyone slept, Cacus stole 4 bulls and 4 cows from Hercules’ herd of cattle, and brought them to his cave.

Hercules discovered the theft the next morning. The remaining cattle called out as they were moving out and the stolen ones answered loudly back from the cave.

In his wrath, Hercules stormed the cave, and after much ferocious sound, black smoke and violence, he slew the thieving monster.

He then recovered the animals from the cave and resumed his journey back to Greece, where he delivered the cattle to King Eurystheus.

Hercules of the Romans

Evander and his tribe were so grateful to Hercules that they dedicated an altar to him called “Ara Maxima” where they performed festive rites to celebrate him and his good deed.

Romans continued to celebrate the cult of Hercules well into the age of imperial Rome. The Ara Maxima was located in the Forum Boarium until it burned down during the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE.

I wrote this story based on the writings of Virgil (Aeneid), Giorgio Vasari (Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors & Architects), and Michael David Montford (Carving for a Future: Baccio Bandinelli…) – Reference (11, 12, 13). For a complete list of sources and resources used on this webpage, please see the References page.

Related Posts

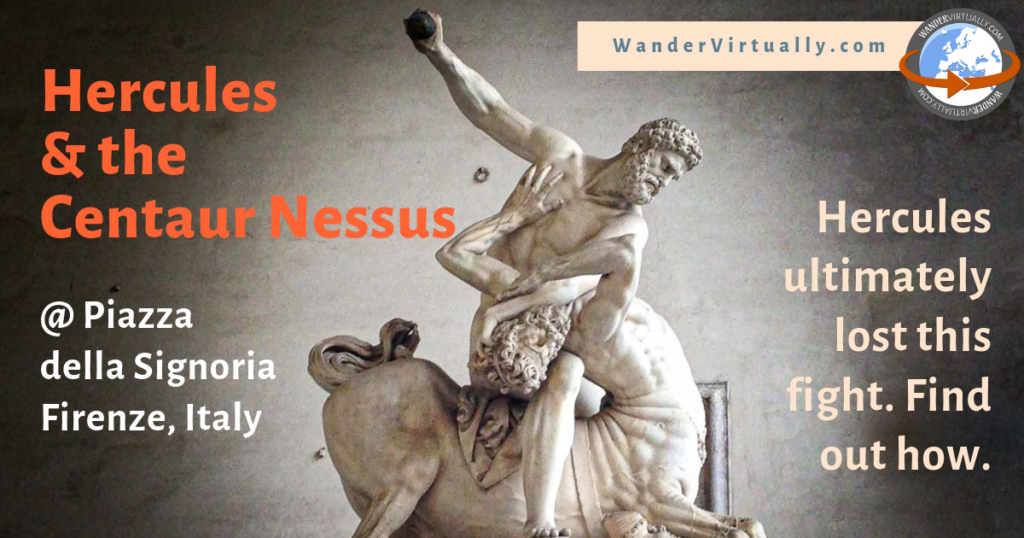

Check my post on Hercules and the Centaur at the Piazza della Signoria

Find out more about him: The Story of Hercules – an Imperfect Hero

Take this 2-mile Firenze sightseeing walk and watch the sunset over The Florence Skyline from San Miniato al Monte.

Sampling Italian cuisine should be part of your Italian travel experience. But, are you ready for the Italian menu challenge? Get help from my post on Lunch & Dinner: Navigating the Italian Restaurant Menu.

I use simple, inexpensive, but useful tools for travel. Find out what I pack for my trips.

Visit the Italy page for more stories and travel tips …

BELLA ITALIA

Fascinating ancient stories.

Practical travel tales and tips.