Cellini’s Perseus and Medusa sculpture is a valuable masterpiece. But he got the short end of the stick when Cosimo I de’ Medici only paid 3,500 gold crowns for it.

Featured photo: Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus and Medusa bronze sculpture @ the Loggia dei Lanzi. Piazza della Signoria – Florence, Italy.

Table of Contents

- Cellini’s Sculpture

- Benvenuto Unveils His Bronze Masterpiece

- What Does It All Mean?

- Cellini – In His Own Words

- Cellini’s Detractors

- A Tale of Two Patrons

- How Much Is That Perseus In the Loggia

- Bandinelli’s Reluctant Compliment

CELLINI’S SCULPTURE

Benvenuto Unveils His Bronze Masterpiece

Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1572 CE), the Florentine goldsmith-turned-sculptor, unveiled his magnum opus, the sculpture Perseus with the Head of Medusa, in April 1554. For days, the citizens of Florence marveled at the amazing sculpture and jostled one another to post sonnets eulogizing it.

The sculpture is made of solid bronze. And some pewter, including Cellini’s platters, dishes, and bowls which he threw in during the casting process when it looked like there wouldn’t be enough molten metal to fill his mould.

Four bronze statuettes, expertly wrought, grace the sculpture’s elaborate pedestal: Jupiter (Zeus), Mercury (Hermes), Minerva (Athena), and Danae with the toddler Perseus.

Athena (Minerva) – loaned her shiny shield to Perseus, her half-brother.

Hermes (Mercury) – lent his adamantine sword to Perseus, his half-brother.

Perseus’ father – Zeus (Jupiter).

Danae and Young Perseus

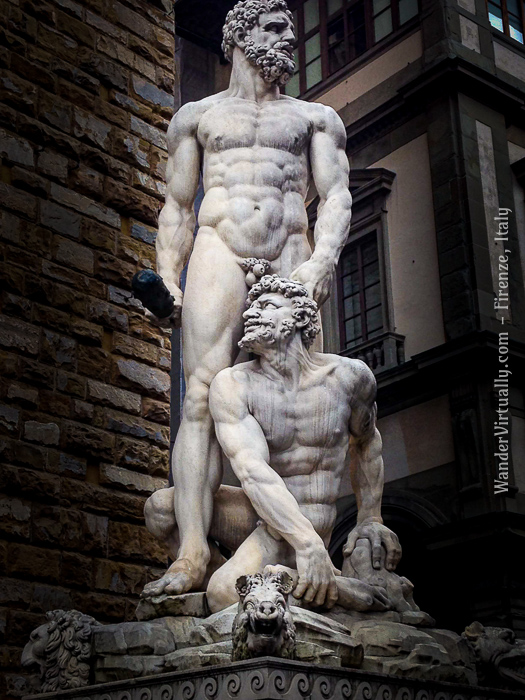

The 10.5-foot colossus stands at the Loggia dei Lanzi in the Piazza della Signoria of Florence. Check out the Google StreetView below. Does it seem to challenge Michelangelo’s David, and Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, the gigantic marble sculptures guarding the Palazzo Vecchio portal? Both seem to be looking at Medusa and have turned to stone!

To view this and other Google StreetView 360 photos in this website:

On mobile phones: View the photo in landscape mode.

On tablets or desktops: The square icon on the upper right corner maximizes or minimizes the photo.

Magnify the view: To zoom in or out, use the + or – sign on the lower right corner.

Move/Rotate the photo: Use your mouse/fingers to drag and rotate the view around or upward-downward.

What Does It All Mean?

Nine years before the unveiling, Cellini returned to Florence, Italy after a long absence. For several years, he had lived in Paris to work for King Francis I, France’s patron of the renaissance.

Upon returning to his hometown, Cellini introduced himself to Cosimo I de’ Medici. Cosimo I had been installed a few years earlier as the Duke of Florence, a city-state that had recently overcome its resurgent republican rebels. (Later, he would become Grand Duke of all of Tuscany). Unlike his progenitor Cosimo the Elder who ruled Florence a hundred years before him and who avoided explicit displays of power, Cosimo I did the opposite. (Learn more about the Medici of Florence here).

The Duke immediately commissioned Cellini to create a colossal bronze sculpture of Perseus beheading Medusa. In the tradition of allegorical displays of power through art, the Duke wanted a fitting symbol of his victory over his political enemies and an unmistakable warning to Florence citizens who, still, might harbor republican tendencies.

In the myth, Medusa was a Gorgon monster with snakey hair and a stare that could turn men into stone. Perseus, the legendary Greek demi-god, went on a quest to slay the monster. Using a shiny shield that he used as a mirror he was able to avoid looking directly at Medusa. And with a very sharp sword, he beheaded the monster while she was asleep.

Thus, in 16th-century Florence, Perseus’ conquest of the Gorgon Medusa, was a powerful metaphor that conveyed:

Perseus = Absolute Power of the Medici Monarchy.

Medusa = Defeated republican enemies.

Before it became a political metaphor, there’s more to the story than Perseus’ beheading of Medusa. Read the short story I derived from the most ancient sources, The Story of Perseus, Retold.

CELLINI – IN HIS OWN WORDS

Cellini wrote a revealing autobiography in which he recounts the intrigues, mercurial passions, and pecuniary challenges of his creative endeavor. He was already famous as a goldsmith with no equal. However, he wanted to be known as a successful sculptor in the same league as his idol, Michelangelo. The Perseus & Medusa project seemed to be the perfect opus for this ambition. But little did he know that it would tax him physically, emotionally, and financially.

Cellini’s Detractors

Commissions at the Medici court were competitive. Certain individuals insinuated to the Duke that although Cellini was undoubtedly great with small statuettes as a goldsmith, his talents may come up short when it came to statues of a larger-scale. Others just didn’t like the arrogant, self-righteous, and opinionated Cellini. It wasn’t long before the hot-tempered artist came into conflict with these purveyors of malice.

He hated Baccio Bandinelli the most, and considered him “… the foulest villain who ever breathed…”.

Bandinelli created the colossal Hercules and Cacus sculpture installed outside the Palazzo Vecchio. In a famous altercation between them in the presence of the Duke, Cellini criticized Bandinelli’s sculpture as one “with such poverty of art and so ill a grace, that nothing worse was ever seen”. He described Hercules’ muscles and body as “not portrayed from a man, but from a big sack full of melons.”

To which the furious Bandinelli yelled back, “Oh, hold your tongue, you ugly sodomite!”

It is perhaps this allusion to his sexuality that pained him the most. For although Cellini had numerous mistresses, historians point to vague incidents in his autobiography concerning affairs with young men. These seemed to implicate a bisexual disposition in the artist.

A Tale of Two Patrons

In Cellini’s stories, the Duke was very supportive and gave him a lot of praise. Yet, Cosimo I was also quite stingy. While he gave Cellini a house with the necessary workshop to build the sculpture, he declined to fund Cellini’s repeated requests for additional helpers. As a consequence, Cellini performed a lot of non-creative manual labor for the project which he claimed, drained his strength.

In contrast to the Duke, King Francis I apparently gave him as many workmen as he needed for his workshop. He drew a yearly salary of 700 gold crowns in France – whereas Cosimo I gave him only 200 gold crowns. For every object of art that Cellini created, the French King awarded him additional generous gratuities which he received promptly. For instance, King Francis paid him 1,000 gold crowns for his most famous work (next to the Perseus & Medusa) – the golden Saliera (Cellini Salt Cellar, 1543) – even before he started the project.

Cellini always bemoaned his “misfortune” working on the Perseus and Medusa for Cosimo I. He deeply regretted having returned to Florence and having abandoned his position in Paris, working for the more generous King Francis I.

“… cursing the unhappy day which brought me to Florence. Too well I knew already the great and irreparable sacrifice I made when I left France; nor could I discover any reasonable ground for hope that I might prosper in the future with my prince and patron. From the commencement to the middle and the ending, everything that I had done had been performed to my great disadvantage….”

— Cellini (Autobiography, ch. XC)

Cellini wrote that there was a time when Cosimo I was in arrears in paying the monthly salaries of his employees – until he became very ill one day. Thinking that he was about to die, he decided to settle all the unpaid salaries to everyone.

How Much Is That Perseus In the Loggia

As for the Perseus & Medusa sculpture – Cellini struggled with his pride in putting a price on this work. He and the Duke did not have a prior agreement before he started the project. The self-conceited artist believed that once the sculpture was done, its value would be unquestionably high and self-evident.

As he put the finishing touches to the stunning single-piece bronze masterpiece, he believed that no one else could have done the feat of casting it. (Not even the divine Michelangelo, who was too old by that time and would not be equal to the back-breaking physical demands of the work). His expectations were very high – as in at least 10,000 gold crowns high.

So it happened that, after completing the sculpture, he ended up haggling over the price with Cosimo and his representatives. The prickly Cellini was quite upset that he had been asked to put a price on his work. Then he was told that 10,000 ducats “could be spent on building cities and palaces, but not statues”.

In the end, a mutual friend had to intervene. Eventually, Cellini and the Duke agreed on a price of 3,500 gold crowns to be paid in monthly installments. Cellini claimed that several years later, he still hadn’t collected the balance of 500 gold crowns from the Medici.

Bandinelli’s Reluctant Compliment

Cellini relates an interesting twist to this story. He was told that the Duke had requested Bandinelli to assess the value of Cellini’s Perseus & Medusa sculpture. Bandinelli was unwilling but eventually, reluctantly agreed. He grudgingly stated that it was “rich and beautiful and excellent in execution”. Therefore, he thought that “16,000 gold crowns would not be too much of a price for it”.

The Duke was naturally shocked and enraged. But Cellini never received what he believed to be the true worth of his masterpiece.

AUTHOR’s NOTE

In the 1500s, a gold crown in Florence contained 3.545 grams of gold. Hence, 3,500 gold crowns would have 12,407.5 grams (438 ounces) of gold, and 16,000 gold crowns would have 56,720 grams (2001 ounces).

In today’s crazy gold prices of the year 2020: that would translate in the vicinity of US$600,000 and US$3,000,000, respectively.

Finally, a caveat: we don’t know if the valuations of Cellini’s Perseus and Medusa sculpture included the cost of materials or just the creative work. When sculptors use marble, it was usually quarried at the commissioner’s expense. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to think that the bronze for the Perseus and Medusa (except for Cellini’s pewter dishes) was also provided by the Duke.

This story is based on The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, and Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects (see References 12, 22). For a complete list of sources and resources used on this webpage, please see the References page.

Related Posts

Did you know that Perseus was born of a virgin mother, married an Ethiopian princess, and committed parricide? Read The Story of Perseus, Retold.

Get the story The Medici: Benefactors Of Your Sightseeing In Florence

Check my post on Hercules and Cacus at the Piazza della Signoria

Visit the Italy page for more stories and travel tips …

BELLA ITALIA

Fascinating ancient stories.

Practical travel tales and tips.